Lobster is king these days in Cape Breton waters and throughout the eastern seashore. Although Maine has been the focal point for lobster this last century due to marketing and early access to global distribution channels, Cape Breton and the rest of Atlantic Canada are thriving based on demand from new markets. Like any other product that has ever existed markets change and fluctuate, creating times of bounty and times of hardship. There is a long and diverse history related to lobster that I’ve been delving into over the last few months.

Lobster fishing boat in Main-à-Dieu. Photo Credit: Tom MacDonald courtesy of Google Maps

The Early Years

Lobsters were plentiful on the east coast for hundreds, if not thousands of years. There are reports of lobsters being washed up in the beach during low tide, and after storms, sometimes in piles two feet high. It is said that the Mi’kmaq used lobsters for food, to fertilize their crops and to bait their fishing hook, and sometimes used the cleaned and polished lobster claws as tobacco pouches and even as pipes (from The Spirit Sings, Artistic Traditions of Canada's First Peoples 1827-29).

In his journal entry referencing Cibo (Sydney), Nova Scotia from 1597 English Captain Charles Leigh wrote that "In this place are the greatest multitude of lobsters that ever we heard of; for we caught at one hawle with a little draw net above 140."

References to how lobster were fished during these early times stem from collection by hand along the coast, hook and line dragging, the use of a spear as well as dragging nets in shallow areas. As colonists occupied more of the eastern shore and lobsters became less available practices switched to basket designs brought over from France and specialized hauling boats called smacks. It wasn’t however until the mid 19th century that lobster traps, as we know today, became a more popular way of harvesting as fishing operatord found more success in deeper waters.

Due to their sheer abundance lobsters became a precious source of sustenance during hard times, which gave them a nasty reputation as the poor man’s protein, being labelled regionally as “the rat of the sea”. There are widespread references that lobsters were routinely fed to prisoners, apprentices, slaves and children during the colonial era and beyond. In one Massachusetts town, a group of servants became so upset at their lobster-heavy diet that they took their masters to court and won a judgment protecting them from having to eat it more than three times a week. Afterwards servants allegedly insisted on stipulations in their contracts that they would only be served the shellfish twice a week.

Although widely spread, it is a common misconception that the average European during the colonial period had a distaste for lobster and would not eat it. Revered maritime historian A. J. B. Johnston in his paper The Early Days of the Lobster Fishery in Atlantic Canada references several Cape Breton accounts of Europeans enjoying the taste of lobster, including explorer and trader Nicolas Denys, accounts by French Governor General’s secretary Thomas Pichon, as well those of invading New England soldiers during the siege of Louisbourg.

Johnston also references lobster fisheries in coastal France and lobster markets in England as further evidence that even upscale Europeans were eating lobster and were not just eating bologna, as one local Cape Breton radio host mentioned some time back. Perhaps, just like today, it came down to personal preference during various periods of our long history.

Despite early interests the perception of lobster as a food for the poor persisted into the 1800s. “Lobster shells about a house are looked upon as signs of poverty and degradation,” wrote American observer John Rowan in the mid-19th century. Peddlers in Portland, Maine carried lobsters around in wheelbarrows, selling them on the street to working class Irish immigrants.

Although Nova Scotia holds the record for the world's largest lobster caught in 1977 and weighing 44 lbs, it also used to be home to the world's largest lobster trap in Cheticamp that stood until the 1990s. There has been some recent talk about bringing the largest lobster trap back. Photo credit: americansguide.ca

The Start of the Lobster Industry

Lobster first appeared on menus in the 1850s and 60s as a bargain dish in the salad section of stores. The going rate was half that of chicken salad. Accessibility to lobster was still mostly limited to coastal communities. That changed with the invention of the stamp can in 1847 which allowed food to be stored for future use. Canneries soon followed.

Early canning started in Maine and then spread to the rest of the Atlantic seaboard.The first Cape Breton canneries opened in Richmond County in 1872 and then in other parts of Cape Breton the following year (Nineteenth Century Cape Breton: A Historical Geography Hornsby 1992). At first the canners had difficulty convincing fishermen to catch lobsters and an even harder time persuading shop owners to buy the canned goods, but they soon realised the market for a low-cost protein food that could be stored and transported. Soon the canneries dotted the landscape of most coastal communities, creating much needed jobs and a thriving industry.

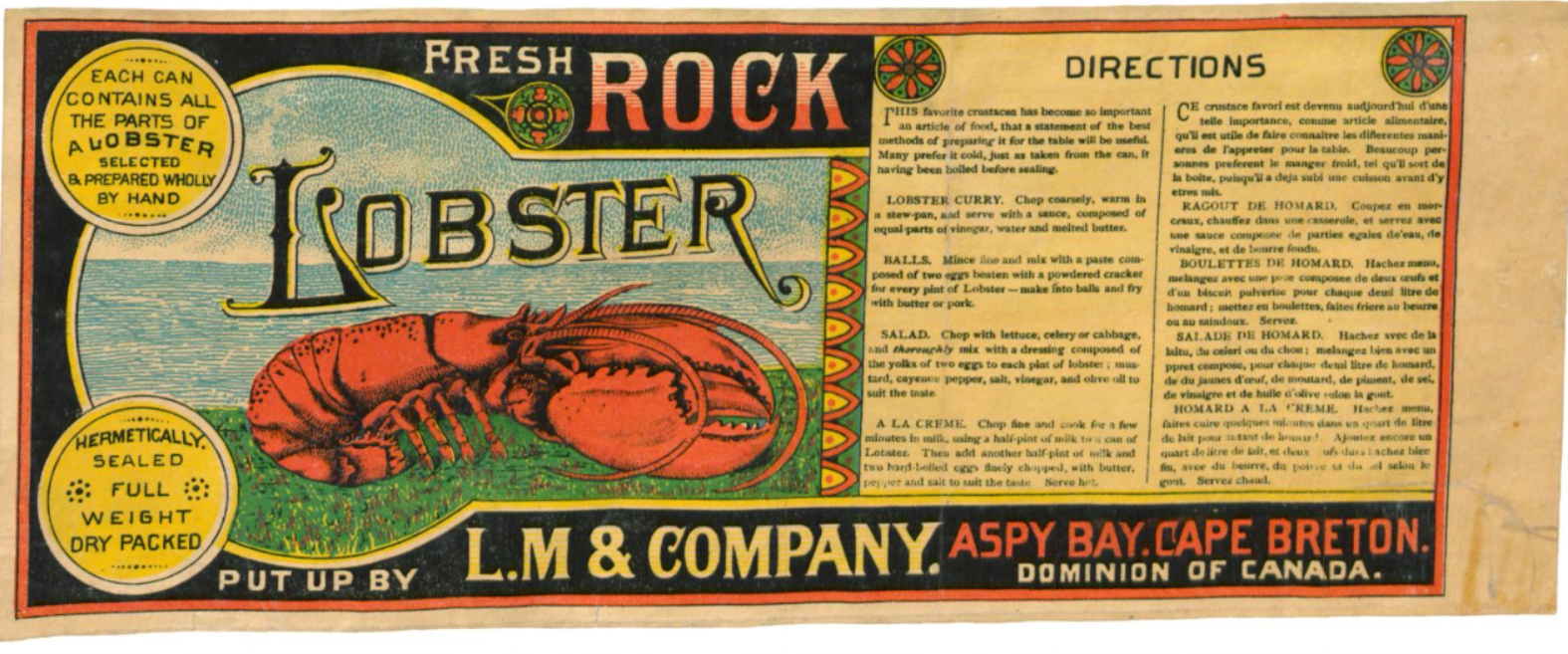

Early packaging label from Aspy Bay, Cape Breton that includes a recipe for lobster curry! Photo Credit: Nova Scotia Archives

After changing the landscape and dynamics of small fishing communities for thirty years, the canning industry eventually waned across the Atlantic seaboard. At a time where lobster fishing was vastly unregulated the resource dwindled due to increased pressure from industrial processing. In the beginning about one to two lobsters were needed to fill every one-pound can. Lobsters used for manufacturing were around 3-6 pounds each while the smaller lobsters were simply thrown back. Just ten years later fishing practices became so aggressive that lobsters couldn’t survive long enough to grow beyond two pounds. Now it took ten or more younger lobsters—many which had never reproduced— to produce a one-pound can. In a nut (lobster) shell, the cost of shelling outweighed the profits, pushing most small canneries out of business.

As the canneries struggled other opportunities emerged by the 1890s. With increased accessibility to markets the lobster started to shed its notoriety as a lower class food, gaining a following among upper class diners, particularly in Boston and New York City. Tourists to the east coast in search of unique experiences elevated the lobster further, finding a new appreciation for the one to two pound lobsters that now fit nicely on their dinner plates, and were willing to pay top dollar. New methods of refrigeration and ice packing allowed fishermen to ship live lobsters inland as far as Chicago, St. Louis, and even to England, where they sold for ten times the original price. As supply struggled to keep up with demand the prices for lobster went through the roof. Between 1889 and 1898 average per-pound prices quadrupled, then jumped again in 1905 (The Lobster Coast, Woodward). Only the ever-increasing prices kept an environmental disaster from occurring from overfishing.

The market remained strong up until the Great Depression in the 1920s, when most could no longer afford the dish in restaurants. Canneries had a revival as there was once again the need for a cheap source of protein for the population, including military troops. After the depression the market rebounded as lobster had instilled itself as an upscale, fancy meal that families could partake in from time-to-time. Interest continued to rise through the 1950s and 1960s. As the rise in the market for live lobsters in the United States the canneries started to disappear once again on the landscape, and canned lobster eventually was gone from most of the Maritimes. There is a great article in Cape Breton’s Magazine about lobster fishing in Cape Breton (Main-a-Dieu, Mabou, Grand Etang) up to the 1950s and 1960s: http://capebretonsmagazine.com/modules/publisher/item.php?itemid=739

Co-op lobster canning factory in Grand Etang circa 1940 from Cape Breton's Magazine

Packing lobster in factory near Cheticamp ca. 1959 - NS Archives

The prices at market haven’t always demonstrated a net benefit to local fishermen, most notably in 1909, when fishermen tied up their boats and went on strike for better prices from canning companies. This, in itself, was a strong demonstration of early organisation and cooperation among the fishing community in the early years. Unfortunately, at the time, communities that did not give up and give in suffered greatly. The American canning company Burnham & Morrill mothballed its factory for the 1909 season leaving no one to buy Gabarus lobsters. The fishermen in Gabarus responded by establishing a cooperative cannery in Gabarus Bay at the now abandoned community of Gull Cove. All-in-all the price for giving up valuable days on the water to strike resulted in no price increase but a promise of a government inquiry. (Historicizing the Lobster Fishery Tie-Up, Morton, 2013). Another tie-up happened more recently in 2013 where fishermen negotiated a modest increase in lobster prices.

Gull Cove lobster factory. circa 1951. Although the community has been abandoned for many years, the stories persist. Photo credit Albert Albie MacDonald

Present Day

Today the lobster fishery is just as volatile as it ever has been. The success of the industry not only depends on the success of the resource, but also market competition and positioning; all playing out on a global scale.

China has become a significant player in recent years with their growing middle class that wants the best that the world can provide delivered to their doorstep. In 2016 Nova Scotia exported more than $218 million worth of seafood to China. It is expected that this market will continue to grow as China invests in more processing plants and has lowered tariffs this year.

The marketing piece is one of the most intriguing elements. There has been ongoing, often ravenous competition between the powerful marketing of Maine lobster and cheaper Canadian lobster. The topic even became part of the mainstream in 2009 with celebrity chef Gordon Ramsay on his show Kitchen Nightmares, where he vehemently scolds an establishment for substituting Maine lobster for Canadian lobster. He harnesses some sort of super-power that allows him to detect the difference by sight (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mkSR7ExMDPc).

This was quickly followed up by the emergence of Fourchu lobster, the proclaimed “Rolls Royce of Lobsters” that gained traction in 2010-2011 due to the extraordinary efforts of Dorothy Cann Hamilton, the founder of the International Culinary Centre. She claims that their exquisite taste is because “they're raised in exceptionally cold and clear water, so they grow slowly, and they're harvested before molting, so their meat is firm, with a complex taste that's not overly sweet.” The lobsters were transported to New York City for distribution to several upscale restaurants. http://gothamist.com/2012/05/30/test_driving_the_rolls_royce_of_lob.php#photo-1

With any product these days it is very difficult to sift through the smoke and mirrors.What people care about is the taste, the story behind the product, the ethical practices that are employed, and, of course, the cost. But we are all being constantly manipulated in these areas and much is often romanticised to some extent in the name of big business. As Mary Roach points out in her 2013 offering Gulp, taste is subjective. “It’s ephemeral, shaped by trends and fads. It’s one part mouth and two parts ego”. This holds true with perceptions of lobster in the 18th century or in the present day. She goes on to point out that studies conducted with wine and cost, and how, during blind taste tests with experts, least expensive wines regularly outscore the more expensive ones and often the most expensive wines score the worst.

So perhaps the low cost is driving Ramsay’s distaste for Canadian lobster. Perhaps it is something more that speaks to the preferences and acquired tastes of a broader group of consumers. I'm inclined to think he was paid off by the big Maine marketing machine that year. What is clear is that marketing is big business and will continue to be a key driver in the success of our industry and a resource that has helped to define our coastal communities.

Other Sources:

The American Lobster. History of Lobster Fishing and Processing. http://www.parl.ns.ca/lobster/history.htm, 2017

A Taste of Lobster History. http://www.history.com/news/a-taste-of-lobster-history. 2011

I dedicate this article to David Bull, a dear friend that passed away this year. He was instrumental in rejuvenating my interest in culture and history after being subjected to too many school trips to the local museum that involved hours of watching someone churn butter.

Chris Bellemore is a blogger from Ontario that moved to Cape Breton Island and is logging his experiences in this strange and wonderful place. The good, the bad and the ugly. "You see, in this world there's two kinds of people, my friend: Those with loaded guns and those who dig. You dig."

My life in a nutshell, with most of the bad parts cut out:

https://www.facebook.com/chris.bellemore

My music that I work on, sometimes with a few friends:

https://soundcloud.com/crispbellemono Trust me on this. From what the statistics tell me I'm a big hit in Bangladesh and Wales.

6

Log In or Sign Up to add a comment.- 1

arrow-eseek-e1 - 2 of 2 itemsFacebook Comments