It is easy to romanticize the past, especially when monstrous fish are involved, evoking a sense of prosperity, adventure, exploration and facing the unknown. Adventure is a common thread here, and on the surface it seems that the turn of the 20th century in general was all about adventure. We always seek to understand, but with history we have to often ask ourselves the basic question of if we are reinforcing our own values, or coming at it from a true sense of impartiality.

People today, both in Cape Breton and abroad, understand in general that Louisbourg is significant, or what it is “known for”- its historic French fortress that once stood as a strategic seaport and the role it played in the English/French conflict that took place during the 18th century. In an article written by Frederick Edwards in 1941, he stated this very thing while talking about Louisbourg’s other claim to fame in the world - it being the concentration point for Broadbill swordfish in the Atlantic and the epicenter for the swordfishing industry; something that was once just as widely known not only locally, or nationally, but also internationally. It not only brought economic prosperity to the community, but scientific understanding and fame.

Broadbill Swordfish

Swordfish are, at maturity, massive, majestic fish. Cape Breton’s Magazine, issue 4, 1973 described them this way.

“The swordfish is a solitary creature. It does not school, and it is considered rare to find two close together. It is pelagic, which means it lives in the open seas; and it is a warm-water fish, seeking temperatures of 60 degrees Fahrenheit. They are found throughout the tropical and temperate Atlantic; in the Mediterranean; around New Zealand, Hawaii and Japan; and in the South Pacific north to California. In the western Atlantic, it ranges from Jamaica, Cuba and the Bermudas, to Cape Breton Island, entering into the Gulf of St. Lawrence and upon the Grand Banks. They are generally found north only in the warmer months.”

The Commercial Fishing Industry

Large numbers of swordfish once travelled to the east coast of Cape Breton. New England began fishing swordfish off the Scotian Shelf that runs between provincial waters and the Gulf of Maine in the 1880s. The commercial fishery in Canada formally began in 1903. Fishing boats followed the fish from Digby to Dingwall and beyond to the Gulf of St. Lawrence in pursuit of fish, but Glace Bay and Louisbourg (apparently bitter swordfishing industry rivals at the time) were the "hustle and bustle" for activity between 1909 to 1959. Melvin S. Huntington, a past mayor of Louisbourg who kept meticulous diaries of the town during the period from 1896 to 1950, made his first reference to “quite a large member of sword fisherman in port” starting in 1917. He continued to collect detailed information related to the resident and seasonal fishing vessels that called Louisbourg home during swordfish season and their catches throughout the years. It wasn't uncommon to see hundreds of boats in coastline harbours at this time, sometimes over 400 in any given place.

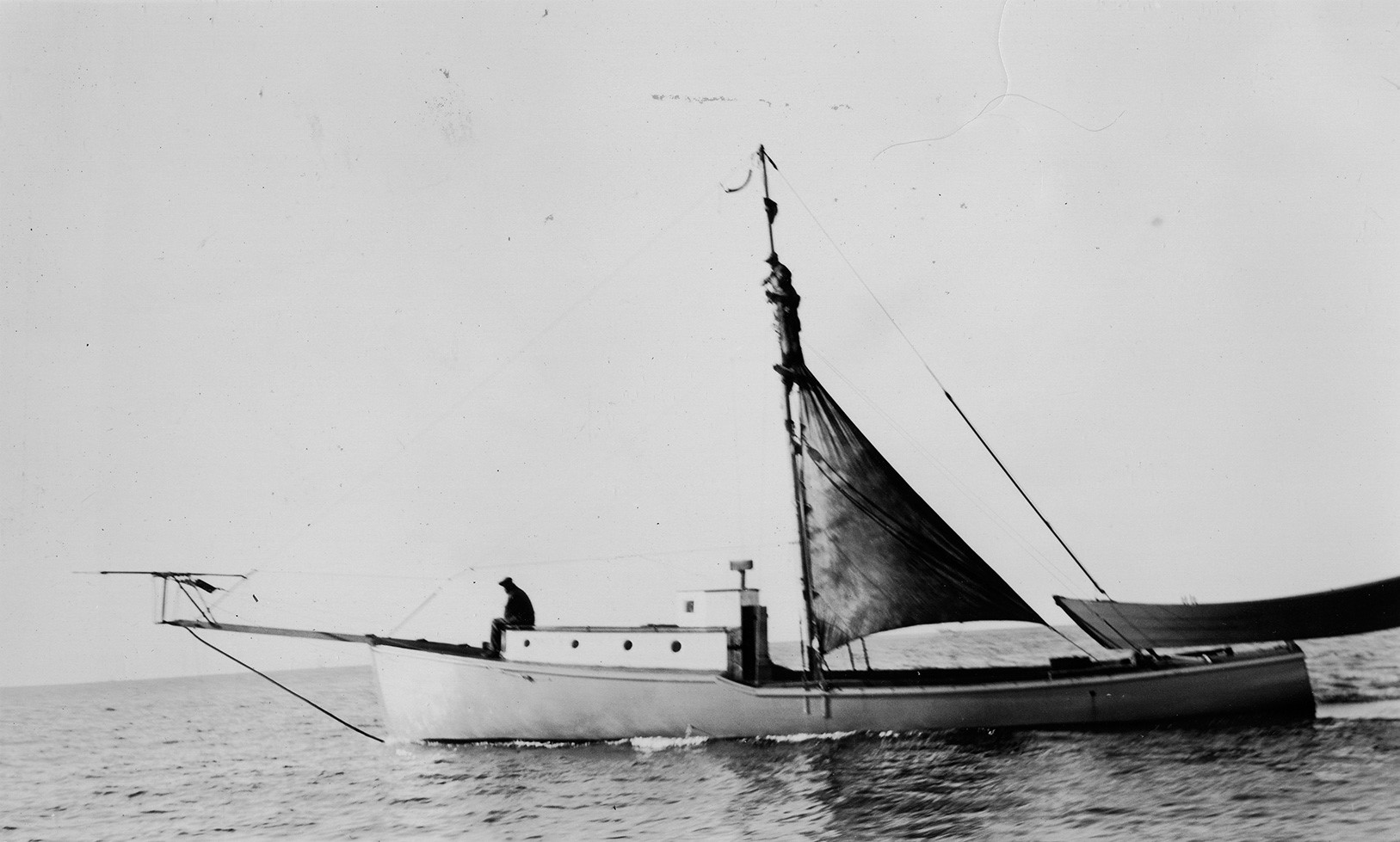

Commercial fishing of Broadbill Swordfish was done with harpoons. Harpoons consisted of 16-18 foot poles attached to a bronze dart called “lily irons” The spear was rigged by rope to a keg. The fish make a habit of lazing about just under the water's surface, known as “finning”. The standard crew for the board consisted of one at the top of the mast as a lookout, one steering the boat and a harpooner at the end of the bowsprit. Over time several boats were retrofitted so that they could be steered from the mast, eliminating the need for a third crew member in calmer weather, however it wouldn't be uncommon to have three members up on the mast looking for fish. When a fish is spotted, the lookout directed the harpooner to sneak up on the fish from behind. When the bowsprit passes over, the harpooner impales the fish.

Picture of swordfish boats on the Havenside side of Louisbourg just up the road from where I live on the way to the lighthouse. Credit: Clara Dennis

A dory was employed to then bring in the fish, but this wasn't without peril.

From The Monitor, Nov 20, 1941, from an article on swordfishing in Louisbourg.

"Many times the business end of the sword has ploughed through a dory. One fisherman tells of a sword ploughing through the bottom of his boat, ripping his trouser leg to the knee."

Many fish could be taken within sight of shore. Fins of the fish could be occasionally seen from the harbours, prompting the boats to go out.

The glory years had started by 1930, with prohibition ending and boats being retrofitted to meet the needs of this new, emerging lucrative market. In 1932, over 2,000,000 pounds of swordfish were landed at Louisbourg, with 40 to 50 people employed in processing the fish at the Lewis & Co. wharf. In August of that year Huntington stated ”swordfish quoted in the Boston Market at 10 cts per pound, which means that the local dealers can pay only 1 ½ cts a pound to the fisherman. This is the lowest price on record. At this time last year the local buyers were paying 10 cts a pound”, which demonstrates that this industry, like all others was both lucrative and volatile. He regularly took count of how many were brought into Louisbourg, as many as 430 one day and 480 another in 1938.

Clara Dennis, well know at the time for her adventures and exploits as one of provinces first native-born travel writers in the 1930s, visited Louisbourg in the mid-to-late 30s and recorded aspects of the commercial swordfish industry as part of her mission to “seek and find Nova Scotia”. Her exquisite photographs, many found in this article, contributed to several of her published books and are now in the care of Nova Scotia Archives. More on her in my article here: https://capebreton.lokol.me/the-adventures-of-clara-dennis---cape-breton-1920s-and30s-photos

Charlie Stacey, Harpooner in Louisbourg. Clara Dennis

Commercial swordfishing boat, Louisbourg. Photo credit: Clara Dennis

Swordfishing boats. Lewis and Company Wharf and building in the background. Photo credit: Clara Dennis

Bill Fiander pointed out a story I missed from Cape Breton's Magazine related to Victor Harpell, a long-time swordfisherman from Louisbourg.

"Capt. V, Harpell of Louisburg struck a swordfish on June 28, 1958, on the southeast part of Georges Bank. The dart broke, part of it remaining in the fish which escaped. On July 20, Capt. T. Wilcox of Glace Bay caught a swordfish on the southeast part of Sable Island Bank. It had a broken dart in it. When the two men later met, they found the two parts of the broken dart fit perfectly, evidence of a migration of 400 miles in 23 days.

Recreational Fishery

Recreational fishing of Broadbill swordfish is quite different. It involves a hook and line, and usually several hours of fighting before the fish is tired enough to be brought in.

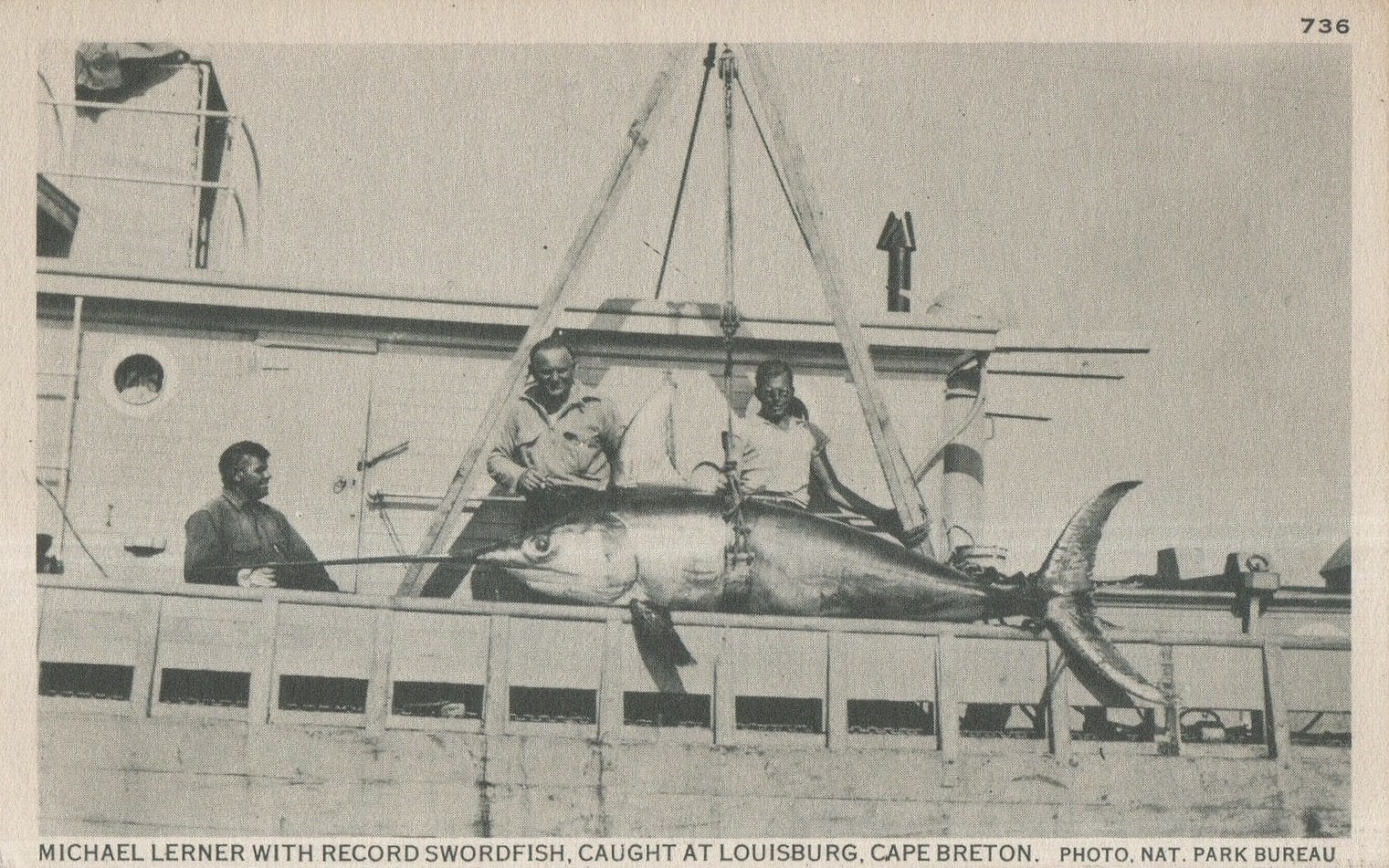

As word of the large numbers of swordfish being fished off of the east coast of Cape Breton spread, it attracted the interest of recreational fishermen in the United States. The first of these to recognize the sport fishing potential was Michael Lerner, the Founder of Lerner Clothing stores in New York. Lerner, who had both strong fishing and scientific interests, approach the American Museum of Natural History to accompany him to Louisbourg.

The Lerner Expedition, including Michael Lerner and Fransesca Lamont. Photo Credit: Gary LeDrew

In July of 1936 he arrived as part of the “Lerner Expedition”, accompanied by scientists Dr. J. Nichols, Mr. H.C. Raven and Ludwig Ferraglio, as well as lead scientist Fransesca LaMont, known later to be Earnest Hemingway’s go-to fish authority and according to a 1952 edition of The Long Island Press, a “general big-game whiz bang.” Bill Lewis from Lewis and Company acted as a go-to between this group and local fishermen. A temporary laboratory was also set up at Lewis and Company’s wharf for sample collection and accommodation of the scientists while they were in Louisbourg. This was the first of two expeditions that Lerner would finance, with some support from the Province of Nova Scotia.

Lerner was the first man to catch a Broadbill in Canadian waters. He landed his first fish, at Louisbourg on Aug 3, 1936 weight 462 ½ lbs. On Aug 6, 1936 he brought in two more, weights; 535 and 601 lbs. Interest in the sport soon skyrocketed. Eventually, dozens of wealthy sports fishermen were coming to Louisbourg annually to try to land a big fish.

Harvey Lewis, another former mayor of Louisbourg, and of the well known Louisbourg family, recounted this time as part of an interview he gave to the Cape Breton Post related to the launch of his book “ Lewis & Company: Memories of a Business, a Family and a Community”.

“When Lerner came to Nova Scotia, the province gave him a boat and even had a photographer go with him,” said Lewis, adding that Lerner’s wife came to Louisbourg with her husband the year after Lerner’s first visit, being the first women catch a swordfish in Canadian waters, stirring up even more interest in the sport."

These exploits soon attracted the major big game anglers of the time to Louisbourg, including writer/ editor for Field and Stream Kip Farrington and author and filmmaker Lee Wulff. Several notable American doctors, lawyers and business people (both men and women) are mentioned landing fish in Louisbourg in the Huntington Diaries, with the accounts spanning into the early 40s.

The Second World War Through Until Today

The lucrative fishery boomed up until the start of the Second World War. With the harbour regulated with a torpedo net and U-boats prowling the coastal waters, as well as many men off to war, the swordfishing in Louisbourg dwindled. Some brave few, including Lerner, and Marion Hasler from Florida, continued to fish the waters off of Louisbourg through 1941. In July of 1942 Huntington wrote “swordfishermen today discovered wreckage including, life rafts, life boats, and buoys and many other articles belonging to a steamer, which is supposed to have been sunk by an enemy submarine last night or early this morning. A signal light usually used on life rafts was still burning when found.”

Gary LeDrew, who grew up in Louisbourg told me a story related to the war and swordfishing from his uncle Al Bussey. Al was fishing off of Scatarie Island. Having a good size fish on he saw a huge shadow beneath the boat, over 200 feet in length which broke his line and freed the fish. Gary says he is 95% sure that this was the French submarine cruiser Surcouf, which was involved in altercations of St. Pierre and Miquelon at the time.

After the war was over, many felt that things would be back to normal with the swordfishing industry in Louisbourg. Swordfish were still being taken throughout the war years, although the recreational fishery had slowed. By that time regular fisherman started to trawl for swordfish with baited hook and line, and ended up catching swordfish of all sizes. Some blame this for the stock plummeting, others the construction of the Canso Causeway affecting the migration patterns of bait fish the swordfish depended on, and yet others pointed to larger boats fishing them off of the Grand Banks before they could come inshore. One thing is clear – the species never recovered, and the unifying consensus is that it was us. There is still a commercial fishery in Nova Scotia, but we are far removed from glory days of legendary monsters being hauled into town daily by the hundreds.

Swordfish bone I found in my Havenside house that started me down the path of this story.

Conclusion

As we contemplate these glory days we should think about how it has shaped the community of Louisbourg today, the good and the bad. Louisbourg, for a small community challenged with outmigration and other rural issues, continues to be a very dynamic place, and although it has officially lost their status as a town, it still, in many ways, functions like one, and has always had a strong legacy of leadership. What do you think it will it be “known for” in the future? What will the new generations of people like Edwards say?

The other thing that came to mind, as I sifted through various bits of research, is how future generations see the decisions me make or decide not make in our lifetime, and what legacy they will be left with. With all of our understanding and technology do we have the ambition and resolve to do better and will that effort be recognised? Maybe if the armies of large fish return one day we will be able to point to something positive. Maybe it will be what we can collectively do in the communities we live in.

I would like to dedicate this story to those at the Louisbourg Historical Society, members past and present, that have worked for many years to keep the stories of Louisbourg alive through a sea of change.

This story, along with many others, are told at the Sydney & Louisburg Railway Museum in Louisbourg, Nova Scotia. Join our Facebook page or follow us on Instagram @slrailwaymuseum as we tell stories and learn and find new things to share with our growing community.

Thank you to so many, including Don MacLean, Gary LeDrew, and Pat Lewis. And to those former mayors that left us such a rich legacy of work to help us understand the past.

Main photo credit: Pat Lewis

Other related articles:

Cape Breton lobster: https://capebreton.lokol.me/the-lobster-food-for-thought

The WW2 plane on top of Jerome Mountain, Cape Breton https://capebreton.lokol.me/the-ww2-plane-on-top-of-jerome-mountain-cape-breton

The last schooner in Margaree: https://capebreton.lokol.me/the-last-schooner

Gary's Vintage Louisbourg page https://www.facebook.com/VintageLouisbourg/

Abandoned Places and Untold Stories of Cape Breton https://www.facebook.com/groups/518156224947471/?multi_permalinks=1761060267323721¬if_id=1530696915827502¬if_t=feedback_reaction_generic

My music https://soundcloud.com/crispbellemono

9

Log In or Sign Up to add a comment.- 1

arrow-eseek-e1 - 2 of 2 itemsFacebook Comments